In a recent interview with Lex Fridman entitled “Dark Matter of Intelligence and Self-Supervised Learning,” outspoken AI pioneer Yann Lecun suggested the next leap in Artificial Intelligence (AI) will come from learning in lower-dimensional latent spaces.

“You don’t predict pixels, you predict an abstract representation of pixels.” - Yann Lecun

What does he mean and how is it relevant to the future of AI?

Let’s back up and consider the context in which this statement was made. Yann was discussing the limitations of current AI systems, particularly those based on deep neural networks. In a previous article, we touched on one such example — Large Language Models (LLMs). LLMs have demonstrated impressive performance across an array of language-related tasks. So popular, a recent AWS study found a “shocking amount of the web” is already LLM-generated. This is problematic, as LLMs trained on this kind of synthetic content break down and lose their ability to generalize. A recent Nature article described this “model collapse” phenomenon in detail.

But Yann wasn’t just talking about LLMs. He was making a broader point about how these systems represent the world. Specifically, he was talking about a reliance on high-dimensional data and the need to move towards learning in lower-dimensional “latent spaces.”

The problem with high dimensions

Contemporary models typically process raw sensor data like pixels, point clouds, or discrete tokens of text. These representations are big, complex, and noisy; they contain a lot of irrelevant information that makes learning computationally expensive, inefficient, and brittle. Tiny changes in lighting, for example, can throw off an image processing model, even though this information isn’t really related to what the object is in the real world.

If you think about it, this is exactly not how humans learn. We don’t process every little detail in our environment. No, we pull out the important features and ignore the things that don’t matter. Consider the example of catching a baseball. As it falls towards you, you’re not paying attention to the color, texture, or even shape of the ball. You’re certainly not thinking about the equations of motion that govern its flight. You’re focused on a few key features — where it is relative to your glove (in 2D space) and how much bigger it’s getting (in 1D space). From this, you make predictions about its path and adjust the position of your glove. The rest is noise.

While simple dimensionality reduction techniques (like, for example, Principal Component Analysis) reduce complexity, Yann’s point is different — the goal is not just compression, but the discovery of causal abstractions that explain why the world behaves the way it does.

Learning latent spaces

Incorporating latent spaces into learning is not a new idea. They are already foundational to how many generative models work. Some diffusion models, for example, run certain processes in compressed latent spaces. Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) do something similar, mapping meaningful representations of data from compact latent spaces; these can then be manipulated to control the generation process (e.g., add a hat to a person’s head).

Existing uses of latent spaces are largely static and domain-specific. For instance, a latent space trained to recognize cats does not help a model understand gravity or motion. Yann argues that truly intelligent systems need to learn latent representations of the physical world as well. These latent spaces capture the essential structure of the environment so the models can make accurate predictions when the little things change. He lays out a blueprint in “A Path Towards Autonomous Machine Intelligence”.

Why this matters for the future of AI

Surveying the current landscape of AI, one might be forgiven for thinking the future is all about bigger models, more data, and faster hardware. If Yann is correct, the future of AI will not be written in pixels or tokens, but the invisible spaces beneath them — abstract structures that capture how the world works while looking nothing like it.

We will see new architectures and methodologies that prioritize learning these latent spaces. Models will become more flexible and robust as they learn to focus on the underlying structure rather than surface-level details. They will need less data, burn less compute, and start to feel more like us.

Our work

We are exploring these concepts in our work on swarm robotics. In “Flocks, Mobs, and Figure Eights: Swarming as a Lemniscatic Arc”, we stabilized a swarm of agents in 3D space by controlling them indirectly through a 2D embedding space. This approach was motivated by a desire to use well-established linear control policies in reduced dimensions while preserving all of the functional properties of the swarm. We later generalized this approach for a broader set of curves in “Emergent homeomorphic curves in swarms”, where we reconceptualized this embedding as a latent space that captures the essential structure of the swarm.

After exploring some of the properties of the latent space using dimensionality reduction techniques like Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP), we are now working to apply reinforcement learning (RL) to control the orientation of the swarm by manipulating the latent space.

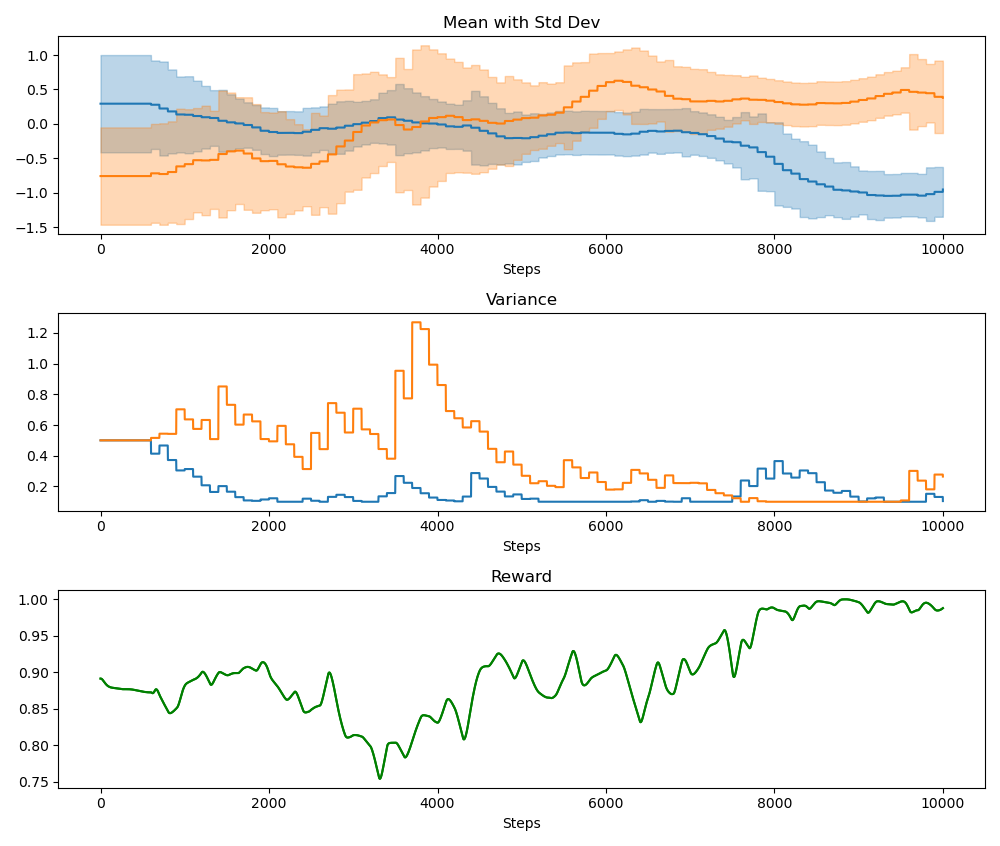

As a proof of concept, we applied Continuous Action Learning Automata (CALA) to learn the optimal orientation of the latent space and reported the initial findings here. Collective learning was coordinated by a randomly selected leader agent. Below are two figures demonstrating, first, the evolution of the probability distribution functions for the two orientation parameters (altitude and azimuth) over time, and second, the combined rewards for each parameter over time.

We have since incorporated this approach into our more general Multi-Agent Simulator (m-a_s) and are working on the following problems:

- Moving away from a leader-follower approach and towards more decentralized coordination of learning outcomes.

- Investigating more complex tasks.

- Exploring more sophisticated learning techniques.

- Analyzing stability and convergence properties.